COOPERATIVE EXTENSION

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA

ENVIRONMENTAL TOXICOLOGY NEWSLETTER

"Published Occasionally at Irregular Intervals"

Vol. 17 No. 1, JANUARY 1997

In This Issue

"Introduction"

"This year marks the 16th for publication of the Environmental Toxicology Newsletter and I am hoping that we can continue with it until we reach at least volume 25. For all this time, the one individual who is most responsible for the success of the newsletter, it's fine appearance, and timely delivery after completion, is Sandy Ogletree, the Extension Toxicology Administrative Assistant at UCD. In these times when our administration is "pulling back" percentages of support budgets for specialists in California, we should all remember that our excellent support staff (and most of us have a person like Sandy) are vital to the success of CE programs.

I have a question which will follow a short account of a recent fiasco in which I participated. For years, I have been utilizing computers for office work and program delivery and have religiously upgraded as new software became available. Last month, I installed an upgrade for the operating system on my laptop (which is the only computer I use now). Four days later, I was finally able to get some work done after reinstalling the old operating system. I lost at least 32 hours of useful work time trying to upgrade, and the manufacturer's technical support group was unable to help, despite multiple calls. I realized that I have reached the asymptotic part of the productivity curve as far as computers go, and will not "upgrade" an operating system again. When I get a new computer, I'll get it already installed and working. For me, the "enhanced" productivity is far less than the time lost during installation and "adjustment". I think this will happen to most of us, or already has, so my question is; "have you reached the asymptotic portion of your productivity curve?"

Sprouted Seeds and Foodborne Illnesses: Implications for Seed Growers

After months of searching for the food responsible for a massive outbreak of foodborne illness in Japan, the Japanese Ministry of Health announced in August that sprouted radish seeds have been implicated as the food responsible for the E. coli O157:H7 infections. More than 9,000 people have been infected and nine people have died.

This outbreak is not the first associated with sprouted seeds. In 1995 alfalfa sprouts were implicated in an outbreak of salmonellosis in Oregon, British Columbia, Vermont, and Denmark. In 1994 contamination of alfalfa sprouts was blamed on a large outbreak that involved people in 27 states and Finland. These large outbreaks occurring around the world have focused attention on how sprouts get contaminated and on ways to control the risks of illness.

If seeds are contaminated with small levels of pathogenic bacteria such as Salmonella or E. Coli O157:H7, the sprouted vegetable seeds can contain very high levels of the bacteria, sufficient to produce illness. This is because bacteria reproduce extremely rapidly when they have optimum levels of moisture and warmth, such as the conditions necessary for germination and sprouting. For example, research conducted at the University of Georgia found that Salmonella levels increased from 1,000 cells per gram in the seed to 10 million cells per gram following germination and sprouting (which involves keeping the seeds warm and moist for 5-7 days).

Sprouts are rarely cooked or even washed prior to eating, so any bacteria that grow during the sprouting process are consumed with the sprout.

People in Japan use radish sprouts (called Kaiware) for salad and serve them with meat and fish. The taste is a little hot and bitter, so small amounts are used with many kinds of foods. It may, for example, be served as a side dish with steak and fish and to top cold Chinese noodles or the Japanese style of pasta. Kaiware is used sometimes also with raw fish dishes (sashimi, sushi). The hotness complements oily fish such as tuna and bonito.

Government regulators and food safety educators have dual tasks: protection of the lives of people who eat the food and protection of the livelihood of those who produce the food. Our experience from many other food safety "crises" is that the best way for an industry to protect the livelihood of its producers is to quickly take positive steps that send a message that the health of the people who eat the food is at least as important as the livelihood of the food’s producers. Denial is almost always counterproductive, even if the targeted food is later absolved of blame. It is also counterproductive to decide, "It’s someone else’s problem." For instance, the source of the contaminated radish seeds is not known. However, all who produce radish seeds will likely feel the impact; thus, the entire radish seed industry worldwide should respond.

In the food industry, Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) is the term used for examining each step in the chain of the production of a food, pinpointing the significant safety hazards, and determining the ways to control the hazards. A national committee has used the HACCP approach to determine the ways that pathogens get on fresh produce. An examination of the committee’s findings may be helpful in thinking about the potential hazards on seeds for sprouting.

Preharvest, the potential hazards were listed as manure used for fertilizer and bodily waste from wild or domestic animals or humans, contaminated irrigation water, and human handling. Postharvest, the potential hazards include human handling, ice and wash water, wild and domestic animals, transport trucks, and temperature abuse.

Conducting a similar HACCP analysis of each step in the production, storage and transportation of seeds for sprouting is the best way to identify where seeds might become contaminated with pathogenic bacteria.

In summary, the key question for all people involved in the growing and marketing of seeds and sprouts for human consumption is how to avoid contamination of the seeds and/or how the seeds can be sanitized to kill pathogenic bacteria (and still retain the sprouting ability). We suggest a proactive industry response, using a HACCP-based approach as well as funding research on ways to assure safety of sprouted seeds.

REF: Agricultural and Environmental News, 126, August 1996. Authors Val Hillers and Richard Dougherty are Extension Food Specialists at Washington State University.

Neglected but Common Sense Steps to Prevent Foodborne Illness

Through the distribution of handouts and verbal communications, veterinarians educate their clients in countless ways. Veterinary practitioners frequently communicate public health concepts. For example, they not only explain toxocariasis risks from kittens and pups but also reduce these risks by administering appropriate deworming medications.

"A Quick Consumer Guide to Safe Food Handling" is a booklet available through the FSIS (Food Safety and Inspection Service) by contacting the USDA’s Meat and Poultry Hotline number — (800) 535-4555. The booklet provides useful consumer information on storing food properly by refrigeration and freezing; preparing raw food without cross-contaminating it; recommended temperatures for cooking meat, poultry, fish, and egg products; serving food safely; what should be done with leftovers; and how long perishables are good in refrigerators and freezers after a power outage.

Another important, frequently overlooked procedure for preventing foodborne illness is basic hand washing. This concept has been part of public health prevention concepts for many years. Washing minor cuts and lacerations with soap and water has been promoted in basic school health classes and first-aid courses. Veterinarians (and physicians) know that washing animal-bite wounds not only helps prevent common infections but also helps curtail the likelihood of virus infection, when the cleansing is done promptly and vigorously. Toxocariasis may be prevented by children washing their hands after playing with pets. People may also avoid Salmonella infections by washing their hands after handling turtles, iguanas, snakes, lizards, and other reptiles.

A Feb 5, 1996 Wall Street Journal article pointed out numerous, surprising reports in various prestigious medical journals (e.g., Journal of the American Medical Association, Lancet) linking the breakdown of basic hygiene to outbreaks of bacterial and viral illness in human hospitals, nursing homes, and child-care centers. A large part of the problem - hospital, nursing home, and day care center staffs, including physicians and nurses, do not wash their hands frequently enough between touching patients.

Foodborne illness prevention is no exception. To help prevent ingestion of harmful organisms (e.g., Salmonella, Campylobacter, Escherichia coli O157:H7), consumers need to wash their hands after using the toilet, after diapering the baby, before preparing meals, before serving meals, before eating, before and after handling raw foods - especially meat, poultry, and fish products, and after playing with or touching pets or livestock.

For some reason, the message that hand washing could reduce exposure to a host of pathogens is often ignored. In an era when bacterial resistance to antibiotics is evolving at an alarming rate, the practice of washing hands (as well as washing cooking utensils, countertops, kitchen sinks, dishes, and cutting boards) should be second nature ... just like it is in veterinarians’ offices between patients, and most certainly, in surgical suites. Health education on this subject has been insufficient.

Prepared by Drs. Craig A. Reed, USDA -FSIS associate administrator and Bruce Kaplan, USDA-FSIS public affairs specialist.

REF: JAVMA, 209(6), September 15, 1996

Campylobacter Appears to be Major Cause of Guillain-Barre Syndrome

Campylobacter jejuni, probably the most common human foodborne pathogen, may also be the major precursor to a rare but sometimes disabling disease known as Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS).

As many as 1% of the U.S. population is infected with Campylobacter every year. For most, these infections will result in some form of gastroenteritis, typically diarrhea, which heals within a week.

Although GBS is rare - affecting about two of every 100,000 people in the United States - it has become the most common cause of acute neuromuscular paralysis in this country with the eradication of polio.

The syndrome typically causes an ascending paralysis - starting with a weakness in the feet and ankles and then affecting the legs, trunk, arms, and muscles of respiration. GBS occurs when myelin, the insulating material surrounding the nerves, gets stripped away by the body’s immune system.

Although most people recover from GBS, the effects for many can be serious. Patients with GBS may require weeks or months of acute hospital care followed by an even longer period of recovery in a rehabilitation or nursing home. About 25% will never return to the work force.

Studies done at Vanderbilt University showed a high correlation between antibodies of Campylobacter and GBS.

Because most human Campylobacter infection is acquired from chicken, control of Campylobacter infections in poultry flocks is critical.

To reduce the risk of being infected with Campylobacter, consumers should be educated about proper kitchen hygiene. They should especially understand the importance of cooking poultry products thoroughly. It is not sufficient to barbecue chicken until it is black on the outside, but still pink near the bone. To avoid cross-contamination, utensils and plates which are used to handle raw meat should be washed before using them on uncooked foods such as salads. People should know not to place their thoroughly cooked chicken on the same plate that held the raw chicken and still has raw chicken juice on it - unless the plate is first washed.

REF: Food Chemical News, 38(15), June 3, 1996.

Bacteria/Spoilage Continue as Shoppers Top Food Safety Concern

Bacterial contamination continues to top the list of food safety concerns viewed as most significant by shoppers, according to the just released Food Marketing Institute’s "Trends in the United States: Consumer Attitudes and the Supermarket, 1996." (See following story.)

Concern over pesticide residues appears to be declining, as 66% of consumers labeled the topic a serious concern, down from a high of 82% in 1989 and from 74% in 1995. Another big drop was seen in the percentage of consumers regarding antibiotics and hormones used in livestock or poultry as a serious risk, from 52% last year to 42% in 1996. Concern rose over product tampering, however, with 66% viewing it as a significant risk, compared to 58% last year.

For the first time, consumers were asked whether food handling in supermarkets was a cause for concern, and 41% said they considered it a serious risk.

Baby boomers are a bit less likely to be completely confident in the safety of the food in their supermarket (18% versus 21% overall), the survey found. "On balance, they are slightly more likely than others to feel that food safety threats come from bacterial contamination (19%), chemicals (14%), pesticide residues (19%), preservatives (7%), food processing (12%), and unsanitary handling by supermarket employees (10%)."

REF: Food Chemical News, 38(12), May 13, 1996.

Food Marketing Institute (FMI) Taking Food Safety Lead Even with Shopper Confidence High

In findings from "Trends in the United States: Consumer Attitudes and the Supermarket, 1996," 84% of the shoppers surveyed registered their confidence in the food supply, up from 77% in 1995.

Ninety-two percent of consumers regard food safety as important when they shop, said Michael Sansolo, FMI group vice president for education and industry relations. "There is no larger issue for us or a more sensitive one for our consumers."

Resist the temptation to use food safety as a marketing tool, President Daniel Wegman of Wegmans Foods Markets, urged FMI members. "Food safety should not be used as a competitive advantage, that only sends a negative message about the industry. Rather, each of us should do everything we can to make sure the foods we offer our customers are as wholesome and safe as they can be. When one of us has a problem with customers' health, all of us have a problem."

Twelve states currently require that food handlers be certified and that they have competency and knowledge in foodborne illness and prevention.

The FMI Trends survey is available for $35 for FMI members and $90 for non-members. For more information call 202-429-8298.

REF: Food Chemical News, 38(12), May 13, 1996.

Foodborne Illness FDA's Highest Priority for Consumer Education

The Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) general consumer education program for fiscal years 1995 through 1998 targets the prevention of foodborne illness as the highest priority of the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN).

For foodborne illness, FDA said the public "needs to know what the major food problems are, what government agencies and/or industry are doing to eliminate or control them, and what they can do to protect their own health and safety."

On food labeling, FDA said information specialists should focus on dietitians, nutritionists and health educators and other "multipliers" who may be able to reach all segments of the population. In addition, it should focus on "target" audiences — populations at risk such as older Americans, children and teenagers, people with low reading skills and those on medically restricted diets.

For emerging technologies, FDA said the objective of the education program is to inform the public about the agency’s biotechnology policy "to assist them in making informed judgements." For packaging, the agency said the "major messages" include letting consumers know that FDA supports the goal of recycling waste materials into safe new products when there are safeguards in place to protect the food supply.

On risk assessment and management, FDA said CFSAN "will provide information to the Office of Constituent Operations, Consumer Education Staff, as policy, regulatory or new technology develops." Some issues will be generated by FDA, such as chemical exposures to lead or mercury, or new technology, such as biotechnology or irradiation. Other issues will be generated outside the agency by media, public interest groups or the scientific community, the agency said.

REF: Food Chemical News, 38(14), May 27, 1996.

Adverse Events Associated with Ephedrine-Containing Products - Texas, December 1993 -September 1995

During December 1993–September 1995, the Bureau of Food and Drug Safety, Texas Department of Health (TDH), received approximately 500 reports of adverse events in persons who consumed dietary supplement products containing ephedrine and associated alkaloids (pseudoephedrine, norephedrine, and N-methyl ephedrine). Reported adverse events ranged in severity from tremor and headache to death in eight ephedrine users and included reports of stroke, myocardial infarction (heart attack), chest pain, seizures, insomnia, nausea and vomiting, fatigue, and dizziness. Seven of the eight reported fatalities were attributed to myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident (stroke).

TDH also has received reports of persons who had acute onset of palpitations and fainting after using ephedrine-containing products marketed as "beyond smart drugs" for "euphoric stimulation, highly increased energy levels, tingly skin sensations, enhanced sensory processing, increased sexual sensations, and mood elevations." Although these substances have been sold without warnings or contraindications on the information labels, one label indicated that the product "acts on the same basis as MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-metham-phetamine, "ecstasy") triggering similar but not identical physical reactions in the body." TDH investigators purchased a product labeled "no side effects" that also listed wild Chinese ginseng as the only ingredient. Laboratory analysis indicated that a single tablet contained 45 mg ephedrine and 20 mg caffeine; the label on this product instructed users to take five tablets, representing a total ephedrine dosage of approximately 11 times the usual recommended OTC dosage of bronchodilator products, which contain 12.5 mg-25.0 mg of ephedrine per dose.

Ephedrine-containing products usually are marketed and labeled for weight loss, energy, "pep," performance enhancement, or body building or as a substitute for illicit drugs such as MDMA. They are commonly labeled as "natural" or "herbal" and use common names for herbs as the source of active ingredients (ma huang, Chinese ephedra, and Sida cordifolia—another plant source with small amounts of ephedrine alkaloids).

Ephedrine and associated alkaloids are structurally similar to the amphetamines and, by stimulating adrenergic receptors, can increase arterial blood pressure through both peripheral vasoconstriction and cardiac stimulation. Adverse effects from ephedrine can be variable, and do not always depend on the dose consumed. Serious adverse effects of ephedrine and related alkaloids, such as acute cardiovascular and central nervous system stimulant effects, can occur in susceptible persons with use of low dosages. Other adverse effects associated with the use of ephedrine include palpitations, tachycardia (rapid heart rate), hypertension, coronary spasm, paranoid psychoses, convulsions, respiratory depression, coma, and death. Particularly when used in combinations with phenylpropanolamine (PPA) and caffeine, ephedrine has been associated with stroke secondary to intracranial hemorrhage, seizures, mania, and psychosis. Combinations of ephedrine and caffeine have been documented to have side effects substantially greater than those from the consumption of either compound alone or of a placebo.

In the United States, ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and PPA have been marketed extensively for some OTC uses. For example, preparations containing ephedrine are marketed for oral use as a short-term, OTC bronchodilator for persons with mild asthma. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has proposed to remove oral ephedrine drug products from the OTC market based on their use in the production of illicit drugs (ephedrine is a precursor for synthesis of methamphetamine) and on their misuse and abuse as stimulants and for weight loss. Pseudoephedrine, an ephedrine alkaloid contained in many OTC decongestant, cold, and allergy products, is associated with fewer cardiovascular and central nervous system stimulant effects than ephedrine. PPA, another ephedrine alkaloid, also is contained in OTC decongestant, cold, and allergy preparations and is marketed for use in the United States as a weight-control agent. Dietary supplements can be marketed with no premarket safety evaluation by FDA. For dietary supplements that include an ingredient marketed in the United States before October 15, 1994—such as products containing sources of ephedrine alkaloids— no FDA review is required.

REF: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 45(32), August 16, 1996.

Fatalities Associated with Ingestion of Diethylene Glycol-Contaminated Glycerin Used to Manufacture Acetaminophen Syrup - Haiti, November 1995 - June 1996

From November 1995 through June 1996, acute anuric (no urine production) renal failure was diagnosed in 86 children (aged 3 months-13 years) in Haiti; most (85%) children were aged £5 years. Investigation indicated that this outbreak was associated with diethylene glycol (DEG)-contaminated glycerin used to manufacture acetaminophen syrup.

Most cases were characterized by a nonspecific febrile prodromal (before the onset of renal failure) illness followed within 2 weeks by anuric renal failure, pancreatitis, hepatitis, and neurologic dysfunction progressing to coma. Ten children were transferred to medical centers in the United States for intensive care and dialysis; nine are still living. Of the 76 children who remained in Haiti, only one is known to have survived. Histopathology of kidney tissue from four patients indicated acute tubular necrosis with regeneration consistent with a toxic exposure.

The investigation indicated that at least 79% of patients had consumed one of two locally manufactured acetaminophen syrup preparations ("Afebril" and "Valodon"), which were subsequently found to contain DEG. Glycerin used in the formulation of these syrups was contaminated with DEG. The contaminated glycerin was imported to Haiti from another country.

Editorial Note: DEG, a known nephrotoxin and hepatotoxin, is used in industrial solvents and antifreeze. The mechanism of toxicity is unknown but probably is different from oxalate toxicity associated with ethylene glycol poisoning.

The outbreak in Haiti is the fourth large outbreak associated with pharma-ceutical products contaminated with DEG. Previous outbreaks (in the United States, Nigeria, and Bangladesh) resulted from ingestion of DEG-contaminated sulfanilamide or acetaminophen syrups. In two of the outbreaks, propylene glycol was the contaminated raw material, and in a third, DEG was used as a diluent. A cluster of 14 deaths occurred in India among patients in one hospital who ingested DEG-contaminated glycerin used for control of intracranial pressure.

Glycerin is used as a sweetener in formulations of many pharmaceutical syrups ingested orally. Infrared spectroscopy tests required by the United States Pharmocopoeia (USP) would not have detected this DEG-contaminated glycerin syrup. A gas chromatography method capable of separating and detecting glycerin, ethylene glycol, and DEG can be used to determine that glycerin is free of these contaminants. The outbreak in Haiti emphasizes the need for pharmaceutical producers worldwide to be aware of possible contamination of glycerin and other raw materials with DEG and to use appropriate quality-control measures to identify and prevent potential contamination.

REF: MMWR, 45(30), August 2, 1996.

Surveillance for Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease - United States

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) in humans and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle are subacute degenerative diseases of the brain classified as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. BSE was first identified in 1986 in the United Kingdom (UK), where an epizootic involving >155,000 cattle appeared to have been greatly amplified by exposure of calves to contaminated rendered cattle carcasses in the form of meat and bone meal nutritional supplements. On March 20, 1996, an expert advisory committee to the government of the UK (1995 estimated population: 58.3 million) announced its conclusion that the agent responsible for BSE might have spread to humans, based on recognition of 10 persons with onset of a reportedly new variant form of CJD during February 1994-October 1995. The 10 persons ranged in age from 16 to 39 years (median age at illness onset: 28 years); of the eight persons who had died, five were aged <30 years. In comparison, in the United States, deaths associated with CJD among persons aged <30 years have been extremely rare (median age at death: 68 years). As a result of the newly recognized variant of CJD described in the UK, the Centers for Disease Control updated its previous review of national CJD mortality and began conducting active CJD surveillance in five sites in the United States. These reviews did not detect evidence of the occurrence of the newly described variant form of CJD in the United States.

REF: MMWR, 45(31), August 9, 1996.

Acute Pesticide Poisoning Associated with Use of a Sulfotepp Fumigant in a Greenhouse - Texas, 1995

Pesticide fumigants that eradicate pests but do not damage flowers or foliage can be used to protect market-ready florals. During November 1995, a pesticide applicator worker in Texas became ill during fumigation despite wearing the personal protective equipment (PPE) recommended on the fumigant product label. The recommended PPE may be inadequate to protect workers using sulfotepp fumigants from pesticide poisoning.

Case Investigation: On November 30, 1995, the Environmental and Occupational Epidemiology Program at the Texas Department of Health (TDH) was notified by the Texas Poison Center Network of a 32-year-old man who had visited an emergency department (ED) because of symptoms consistent with acute pesticide poisoning, including headache, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, cough, slight dizziness, sweating, fatigue, abdominal pain, anxiety, muscle aches, chest tightness, drowsiness, restlessness, shortness of breath, and excessive salivation. The patient was a pesticide applicator employed at a greenhouse and had applied sulfotepp fumigants (Plantfume 103 and Fulex) the previous night. Sulfotepp, a highly toxic organophosphate pesticide and cholinesterase inhibitor, is used in greenhouses to control aphids, spider mites, thrips, and whiteflies; sulfotepp does not damage delicate flowers or foliage.

The patient reported onset of symptoms shortly after igniting the sulfotepp fumigant canisters in the first of four interconnected greenhouses where chrysanthemums, poinsettias, and other plants were grown. Despite feeling ill and smelling the chemical, he and three other workers completed fumigating all four greenhouses. He did not seek medical care until the following day. Physical examination at the ED was unremarkable, and he was released without treatment.

The patient was a licensed pesticide applicator and had been employed at the greenhouse for 2 years. Although he had applied other fumigants in the past, this was the first time he had applied sulfotepp and the first time the chemical was used in this greenhouse. During the application, he wore the PPE recommended on the product label, including a laminated full-body suit, rubber boots, nitrile gloves, and a full-face air-purifying respirator equipped with a pesticide prefilter and organic vapor cartridge. He had undergone a qualitative (smoke) respirator fit test in November, and no leakage was detected. A qualitative fit test conducted after the incident indicated an adequate fit.

On December 3, TDH and NIOSH interviewed the other applicators, inspected the PPE, and observed the next fumigant application at the greenhouse. All three applicators reported wearing the label-recommended equipment, and two of these three workers reported nausea and detecting the odor of the chemical during application on November 30; however, they did not vomit or seek medical care.

During the second application, unopened canisters of Plantfume 103 and Fulex were set out in a grid-like fashion within each greenhouse. In accordance with the label instructions, a total of 80 canisters were set out (one canister per 20,000 cubic feet). The internal air circulation system and the exhaust ventilation system were turned off. The internal air circulation system had not been turned off during the previous application because the applicators misinterpreted the instructions. To avoid the smoke, the workers ignited the canisters as they exited each greenhouse, but each canister rapidly generated smoke. After the final canister was ignited, the workers moved to a shipping area not being treated with the fumigant, removed their PPE, and left the facility. The time necessary to complete the application was approximately 45 minutes and, even though all product label instructions were followed, the index patient again reported some symptoms.

Survey of Growers: During December, TDH conducted a telephone survey of greenhouse operators in Texas to assess the prevalence of greenhouse fumigant use and the occurrence of possibly related adverse health effects among workers. TDH contacted 413 Texas companies listed under Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code 5193 (nursery stock for florists and the same SIC code as the greenhouse) and identified 53 companies with greenhouses in which plants were grown. All 53 companies participated in the survey. Of these, 43 (81%) reported ever using fumigants, and 30 (70%) of the 43 reported using sulfotepp. Of the 43 companies using any type of fumigant, 33 (77%) reported that workers used respirators during fumigant application, including five that used respirators with an independent supply of compressed air. Three (7%) companies reported that at least one worker had become ill during the application of fumigants, none of which contained sulfotepp; none of the workers sought medical care for their illness. At two of these three companies, workers wore all label-recommended PPE during the fumigant application; at the third company, workers did not use PPE during the application.

Editorial Note: Although pesticide use in the United States has doubled since the 1960s, the health effects of pesticide use on agricultural workers has not been well documented. In Texas, where occupationally related acute pesticide poisoning is a reportable condition, 247 cases were reported during 1986-1994. However, during 1989-1990, only 20% of cases were reported.

The findings of the TDH investigation indicate that the acute illness among workers in this report most likely was associated with exposure to the sulfotepp fumigant and underscore the importance of reporting pesticide poisonings. Exposure occurred even though the workers followed the pesticide label instructions and properly used all recommended PPE during the second application. Because there was no evidence of oral or dermal contact with the chemical and workers smelled the chemical, inhalation was the most likely route of exposure. Other factors potentially associated with exposure may have included the technique employed in igniting the canisters and operation of the internal air-circulation system during the first application, which may have increased dispersion of the fumigant throughout the greenhouse.

The sulfotepp label instructions state that applicators and other handlers must use "a respirator with either an organic vapor-removing cartridge with a prefilter approved for pesticides (approval prefix TC-23C) or a canister approved for pesticides (approval prefix TC-14G)". In general, such filters do not provide adequate protection against the high ambient chemical concentration and small particle size characteristic of fumigants. In addition, a single type of filter may not be appropriate for all types and forms of pesticides and, in July 1995, NIOSH discontinued certifying cartridges specifically for use with pesticides. The survey findings in this report indicated that many greenhouses use fumigants, most workers use only a respirator, and other greenhouse workers had become ill during fumigant applications, despite the use of label-recommended PPE.

During 1985-1992, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) received 23 reports of illness in persons occupationally exposed to sulfotepp; 70% of these persons were referred to health-care facilities, and 7% were hospitalized.

As a result of this investigation, TDH and NIOSH recommended to EPA that sulfotepp fumigant labels be amended to indicate the appropriate respiratory protection. Label instructions for other pesticide fumigants also may need to be reviewed for appropriateness. In addition, advertising material and labels for pesticide prefilters, cartridges, and canisters should clearly state they are not for use with fumigants. Professional associations and licensing and regulatory agencies should provide applicators with educational materials regarding the safe use of pesticide fumigants, including appropriate PPE, efficient fumigant application procedures, and less toxic pest-control options. Employers should implement comprehensive PPE programs, including selection of appropriate respirators by qualified staff using NIOSH-recommended procedures.

(There were no AChE [acetylcholinesterase] tests done to confirm that the pesticide caused the illness, a major weakness in this study.)

REF: MMWR, 45(36), September 13, 1996.

Heat Illness Compared to Pesticide Poisoning

When a pesticide handler becomes ill from working with organophosphate (OP) or carbamate insecticides in a possible heat stress situation, it can be hard to tell whether the handler is suffering from heat exhaustion or pesticide poisoning. They have similar symptoms, but the treatments are different. The symptoms are compared in the next paragraph.

Comparison of Heat Exhaustion and Organophosphate/Carbamate Poisoning Symptoms

| Heat Exhaustion | OP/Carbamates |

| Sweating | Sweating |

| Fatigue | Fatigue |

| Headache | Headache |

| Confusion | Confusion |

| Loss of muscle coordination | Loss of muscle coordination |

| Nausea | Nausea/diarrhea |

| Dilated pupils | Possible small pupils |

| Dry membranes | Moist membranes |

| Dry Mouth | Salivation |

| No Tears | Tears |

| No saliva present | Saliva present |

| Fast pulse (slow

if person has fainted) |

Slow Pulse |

| Fainting (recovery is prompt) | Coma (can’t be awakened) |

Combined problems of heat illness and pesticide poisoning may also occur. If there is any doubt about the illness, get medical help immediately. Both pesticide poisoning and heat stroke can be life-threatening and require prompt treatment. (From: Access Pesticides, University of Arizona.)

REF: Kansas Pesticide Newsletter, 19(8), August 16, 1996.

Infection with Mycobacterium abscessus Associated with Intramuscular Injection of Adrenal Cortex Extract - Colorado and Wyoming, 1995 - 1996

During March–April 1996, a physician in the Denver area administered intramuscular injections of a preparation labeled "adrenal cortex injection" to 69 patients in Colorado as part of a weight-loss regimen. As of August 7, a total of 47 (68%) of these persons were reported to have developed abscesses (diameters ranging from 0.5 cm to 4.0 cm) at the site of injection (either gluteal [buttocks] or deltoid [upper arm] muscle). An investigation of these episodes by the physician and the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment identified Mycobacterium abscessus as the cause of the infections. This report summarizes preliminary findings of the ongoing investigation, which indicate that injection-site abscesses were associated with contaminated injectable preparations.

This report illustrates the risks associated with use by patients and health-care providers of non-FDA approved products or products from unknown sources. Preliminary information suggests the product is distributed primarily to alternative-medicine providers. Adrenal cortex injections reportedly are used to enhance well-being in persons infected with human immuno-deficiency virus.

REF: MMWR, 45(33), August 23, 1996.

Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality - United States, 1992

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed nondermatologic cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women in the United States. In 1996, a total of 184,300 new cases of and 44,300 deaths from invasive breast cancer are projected among women. To assess trends in incidence and death rates for breast cancer among U.S. women, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) analyzed national incidence data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program and death-certificate data from CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The findings indicate that incidence rates for invasive breast cancer increased among women during 1973-1987 and stabilized during 1988-1992, while mortality rates remained stable during 1973-1988 and decreased during 1989-1992.

Breast Cancer Incidence: In 1992, the overall age-adjusted incidence rate for breast cancer was 110.6 per 100,000 women. The rate for white women (113.1) was higher than that for black women (101.0). During 1973-1992, the overall incidence rate increased from 82.5 to 110.6: rates increased steadily during 1973-1987, and stabilized during 1988-1992. During 1988-1992, incidence rates increased directly with age until age 75-79 years for whites and age 80-84 years for blacks; the rates for whites and blacks were similar for women aged <45 years, but for women aged ³45 years, the rate was higher for whites than for blacks. During 1973-1992, race-specific rates varied: for white women, the age-adjusted rate increased 34% (from 84.3 to 113.1) and, for black women, increased 47% (from 68.7 to 101.0).

Breast Cancer Mortality: In 1992, a total of 43,063 U.S. women died from breast cancer. The death rate was 26.2 per 100,000 women. During 1973-1992, the overall death rate varied; rates were stable during 1973-1988, before decreasing during 1989-1992. During 1988-1992, the overall ratio of black-to-white death rates was 1.2. Rates increased directly with age. For women aged <70 years, the rate was higher for blacks than for whites; for women aged ³70 years, the rate was higher for whites than for blacks. During this period, race-specific rates varied.

During 1989-1992, the rate for white women decreased 6% (from 27.5 to 26.0) and, for black women, increased 3% (from 30.4 to 31.2). During 1988-1992, the state-specific age-adjusted death rate ranged from 18.2 in Hawaii to 35.3 in the District of Columbia.

Editorial Note: The findings in this report indicate that incidence rates for breast cancer increased 34% during 1973-1992. The increase and later stabilization of incidence rates during the 1980s is most likely related to increased use of breast cancer screening methods -- particularly mammography and clinical breast examination, which enable earlier diagnosis of the disease.

The decrease in breast cancer death rates during 1989-1992 may reflect a combination of factors, including earlier diagnosis and improved treatment. For example, screening mammography and clinical breast examination are effective methods for reducing breast cancer mortality among women aged ³50 years. Survival from breast cancer increases when the disease is diagnosed at earlier stages, and from 1974-1976 to 1986-1991, the survival rate for invasive breast cancer increased substantially.

Differences in the race-specific and state-specific incidence and death rates for breast cancer during 1973-1992 may reflect differences in factors such as socio-economic status, access to and delivery of medical care, and the prevalence of specific risks for disease. For example, women in minority populations are less likely than white women to be screened for breast cancer. Although socioeconomic and risk-factor data were not analyzed in this report, the findings underscore the need for further characterization of the burden of cancer for U.S. women in racial/ethnic, geographic, and other subgroups.

Early detection and appropriate treatment are essential to reducing the burden of breast cancer in the United States. CDC’s National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program provides early detection screening and referral services for cancers of the breast and cervix among older women who have low incomes or are uninsured, underinsured, or in a racial/ethnic minority. Additional efforts by this program and health-care professionals are needed to ensure that every U.S. woman at risk for breast cancer receives breast cancer screening, prompt follow-up, and assurance that tests are conducted in accordance with current federal quality standards.

REF: MMWR, 45(39), October 4, 1996.

Two Studies Find Link Between Beta-Carotene and Increased Risk of Lung Cancer in Smokers

The initial findings from two major clinical trials reported in the November 6th issue of the Journal of the National Cancer Institute revealed that supplemental beta-carotene appeared to increase the risk of lung cancer, particularly in current smokers. The two studies tested a hypothesis suggested by observational studies that beta-carotene might reduce cancer risk, and particularly risk of developing lung cancer.

Based on an analysis of the findings of the two studies, the investigators independently advised smokers not to take beta-carotene vitamin supplements. The results do not, however, mean that beta-carotene in food is harmful.

One study, "Risk Factors for Lung Cancer and for Intervention Effects in CARET, the Beta-Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial," was terminated 21 months early, in January 1996, because there was "clear evidence of no benefit and substantial evidence of possible harm." The report stated that there were 28% more lung cancers and 17% more deaths in the active intervention group. The CARET study authors further reported that the combination of retinol and beta-carotene also increased the risk of lung cancer in asbestos workers, most of whom were current or former smokers. They also found suggestions of the association of excess lung cancer incidence in the subgroup of smokers with the highest alcohol intake.

The second study, "Alpha-Tocopherol and Beta-Carotene Supplements and Lung Cancer Incidence in the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study: Effects of Baseline Characteristics and Study Compliance" (ATBC), examined the effects of both alpha-tocopherol and beta-carotene supplementation on lung cancer incidence. The initial study results identified no substantial effect of the alpha-tocopherol intervention, but found increased lung cancer incidence among participants who received beta-carotene supplementation.

An earlier account of the ATBC trial in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1994 reported an 18% excess of lung cancer in participants receiving beta-carotene; it is now updated to 16% excess. The excess was among participants who received beta-carotene supplements for an average of six years. The effect appeared stronger in men with an alcohol intake of one or more drinks daily and may have been restricted to those smoking at least 20 cigarettes daily.

Both studies found some suggestion of association between beta-carotene supplementation and large-cell type lung cancers. The two studies also found that higher lung cancer risk appeared to be unrelated to baseline serum concentrations of beta-carotene, presumably related to participants normal diets at the time they entered the study. Rather, the two studies reported a statistically significant finding that higher baseline serum beta-carotene concentrations were inversely related to lung cancer risk.

REF: Food Chemical News, 38(38), November 11, 1996.

TIDBITS

By 2000, Some 25% of U.S. Population Will Need to Be More Wary of Waterborne Pathogens

Immunocompromised people aren’t just AIDS patients - normally healthy people over 65 often experience a natural weakening of their immune systems, according to enteric virus specialist Chuck Gerba, University of Arizona. In four more years, by 2000, almost 20% of the U.S. population will be over 65, and another 5% of the population will have immune systems compromised by HIV/AIDS, cancer treatments, organ transplants and other medical conditions, he noted.

The combined 25% of Americans will need to be wary of and protect themselves against waterborne pathogens, he added, saying that he believes "there is a limit to how much we can afford to treat municipal water," so susceptible people need to be educated to be able to treat their own water.

REF: Food Chemical News, 38(15), June 3, 1996.

Food Allergies in Children are on the Rise

Food allergies in children are on the rise, The Washington Post noted in its October 1st Health section. Peanut allergy in particular is a growing problem, allergists at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, Md., said, noting that the number of children treated for peanut allergies in their clinics has doubled from 1984 to 1994. In addition, allergists around the U.S. have reported treating more children with peanut allergy in recent years. The reason for the increase is not clear, but some experts believe it may be linked to earlier exposure to peanuts. Many processed baked goods, snacks and other favorite foods of young children are prepared with peanut flour or oil or come in contact with utensils or cooking containers that have peanut residues on them from other products. An estimated 6 million Americans are allergic to foods -- milk and eggs are the food allergies most common among young children, with peanuts and soy next. Most food allergies occur in genetically susceptible people, usually those with family histories of asthma, hay fever and/or eczema, the Post noted.

REF: Food Chemical News, 38(33), October 7, 1996.

Suffocations in Grain Bins -- Minnesota, 1992-1995

Suffocation in flowing grain is the most common cause of death associated with grain storage structures in the United States: during 1985-1989, suffocation accounted for 49 grain- and silage-handling-associated fatalities.

REF: MMWR, 45(39), October 4, 1996.

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) - United States, 1983-1994

For the first time since 1980, in 1994, SIDS declined from the second to the third leading cause of infant mortality. In addition, preliminary mortality data for 1995 indicate that the SIDS rate declined 18.3% from 1994, representing the largest annual percentage decline since 1983 and suggesting that the higher rate of decline observed during 1990-1994 is continuing. This trend may reflect changes in the prevalence of known risk factors and/or changes in the diagnosis of SIDS.

Many of the risk factors for SIDS identified during the 1980s (e.g., low birthweight, young maternal age, and poor socioeconomic status) are not readily amenable to intervention. However, a strong association between the infant prone sleeping position and SIDS had been established by 1990. During 1992, the American Academy of Pediatrics began recommending that parents place infants on their back or side to sleep, and during 1994, the national "Back to Sleep" campaign began promoting the nonprone sleeping position as well as other modifiable risk factors (e.g., breast-feeding was encouraged and exposure to tobacco smoke and overheating was discouraged). Studies in other countries indicated that SIDS rates declined approximately 50% concurrent with decreases in the prevalence of prone sleeping. In the United States during 1992-1995, the SIDS rate declined 30% concurrent with a decrease in the prevalence of prone sleeping from 78% in 1992 to 43% in 1994. Although the prevalence of breastfeeding did not change substantially during the study period, birth-certificate data indicate that during 1989-1994, the prevalence of cigarette smoking during pregnancy declined by approximately 25% (from 19.5% to 14.6%).

REF: MMWR, 45(40), October 11, 1996.

Hunting-Associated Injuries and Wearing "Hunter" Orange Clothing -- New York, 1989-1995

"Hunter" orange (i.e., fluorescent or international orange) is worn by hunters to increase their visibility and to reduce their potential for being mistaken for game. Although education courses for hunters promote the use of hunter orange, hunters in New York are not required to wear high-visibility clothing. The findings indicate that most injured hunters in two-party incidents were not wearing hunter orange. Of the 125 incidents in which the injured hunter was mistaken for game, 117 (94%) were not wearing hunter orange, and six (5%) were wearing hunter orange; for two (1%), hunter orange information was not recorded.

REF: MMWR, 45(41), October 18, 1996.

Some "Best of the Web" Sites

| American Cancer Society: | http://www.cancer.org |

| American Diabetes Association: | http://www.diabetes.org |

| American Heart Association: | http://www.amhrt.org |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: | http://www.cdc.gov |

| Harvard Medical School: | http://www.med.harvard.edu |

| International Food Information Council: | http://ificinfo.health.org |

| Medical Matrix: | http://www.slackinc.com/matrix |

| National Institutes of Health: | http://www.nih.gov |

| National Library of Medicine: | http://www.nlm.nih.gov |

REF: Harvard Health Letter, July 1996.

![]() VETNOTES

VETNOTES![]()

Adverse Reaction to Tilmicosin in Goats

A private practitioner was called to examine 10 adult goats following their purchase, 2 days previously, from a local stock yard. The animals appeared somewhat unthrifty and had nasal discharges. The animals were treated for parasites with ivermectin and for the apparent upper respiratory tract infection with tilmicosin. This antibiotic was selected because of its long duration of activity following a single dose treatment of cattle. Within 30 minutes of injection 3 of the animals died. These 3 were all of apparent Alpine stock. The remaining animals showed no apparent ill effects. The Poison Control Center at the University of Illinois was unaware of any reports of similar adverse reactions in goats but an Elanco representative indicated that the use of tilmicosin in goats in foreign countries has been associated with a high rate of drug-related deaths.

Practitioners should be cautious about extra-label use of tilmicosin in goats. They might contemplate its use for treatment of Pasteurella haemolytica that had proven nonresponsive to other treatments such as penicillin, oxytetracycline or ceftiofur, but owners should be warned in advance about the lack of other options and the risks involved. Practitioners experiencing such drug-related problems should contact the drug’s manufacturer and the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Adverse Reaction Hotline 301/594-1722 during working hours of Monday to Friday, 7:30 - 4:30 EST; 301/594-0797 after hours; FAX 301/594-1812 so that the incident can be documented. The FDA’s ADR (Adverse Drug Reaction) information is published annually in the FDA Veterinarian and is also available through the FDA’s home page on the World Wide Web at http://www.cvm.fda.gov under the Office of Surveillance and Compliance category. The 1994 Adverse Drug Experience report published in the FDA Veterinarian Vol X, No. VI Nov/Dec 1995 cites two reports involving tilmicosin in goats and one in sheep.— Wool & Wattles, OCT/DEC 95. Herd Health Memo, University of Kentucky, College of Agriculture, Cooperative Extension Service 1995-96 #10, April 1996.

REF: Animal Health Spectrum, 7(2), June 1996.

The Best Way to Prevent Foodborne Disease and Enhance the Reputation of the Veterinary Profession

Sidney R. Nusbaum, DVM

(taken from a Special Commentary in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association)

Recently I assisted in an investigation of what is believed to be the largest single-source outbreak of Salmonella newport to have occurred in this country. One hundred eighty-nine patrons of an ethnic restaurant were determined by bacteriologic culturing to be infected, and 891 others were reported ill.

Salmonella newport, a common isolate from chickens, cattle, hogs, and their products, was not isolated from foods in the refrigerators or freezer. The source of the organism was not a single food. The menu dictated that the food be cooked thoroughly, a procedure that would be expected to destroy Salmonella organisms. Obviously, something beyond a single, contaminated, undercooked food was at fault.

The case was instructive and reenforced a well-known, albeit insufficiently addressed, truth, that is, not all foodborne diseases are a direct result of consuming contaminated animal products. And a corollary, the most effective and economical means of controlling foodborne diseases, are most often at the food processing level.

Ignoring or minimizing these truths in the current rush to design and implement on-farm food protection methods is dangerously unrealistic and costly. Certainly, it is essential to develop epidemiologic and surveillance information about the relationship of production to human infection. And it is essential to use that information to protect human health insofar as is practical. But it is required that the programs and information be considered within the full context of the biologic processes and realistic consideration of dollar cost, overall effectiveness, and near- and long-term political effects.

Regardless of new technology, bacteria-free animals or meat products are not possible. It is not reasonable and is scientifically irresponsible to believe that the microorganisms of concern today will not be replaced with other microorganisms tomorrow. Biodiversity and microflora ubiquity are facts against consistent success of on-farm programs. Further, single-organism directed programs tend to consume disproportionate resources and inherently bear unrealistic expectations of success.

We, as a profession or nation, cannot afford the problems that come with ineffective programs. For example, S enteritidis was a prominent human pathogen in the 1930s that diminished in prevalence until the 1980s when it became one of the most common foodborne pathogens. The problem was eggs. A dispassionate review of veterinary and public health responses to its reappearance would show the responses to have been inept, rife with suspect science, and delayed and ineffective regulatory actions.

Even though it was evident early on that most, if not all, of the egg-associated human S enteritidis disease could have been prevented by proper handling of eggs, the public health sector emphasized the role of production, and the veterinary profession permitted itself to undertake to solve the problem at the farm level without adequate information or organization. Consequently, we embarrassed ourselves with questionable science and a control program that obviously could not effectively identify egg contamination or prevent human infection. Today, we witness continuing large numbers of S enteritidis isolates from poultry and human beings.

The struggle to rid the country of bovine tuberculosis is a monumental example of ineffectual science in eliminating foodborne diseases. More than 100 years ago, our predecessors posited that the way to prevent milkborne tuberculosis infection was to remove cows with tuberculosis. This concept was correct, but, as it turned out, impossible in the short term. After failing at the farm level, a processing approach was applied, that is, destroying organisms in milk by pasteurization. Pasteurization not only provided protection from milkborne infection while we worked out the problems of removing the organism entirely, but also provided safety from various other potential milkborne pathogens that are virtually impossible to completely eliminate on the farm.

There is an enormous danger in the road we have started down; without saying so, we are promising too much. Problems of foodborne diseases go beyond pure and applied science and good intentions. If we seek funds to start programs of prevention and disease persists or new diseases appear, we will be labeled as failures by legislators, funders, industry, fellow scientists, and the public.

It is essential to balance our programs. And it is clear that the most effective steps that can be taken to prevent foodborne illness are at the final food handling and preparation level. It is at this level, as at the restaurant I mentioned, that the greatest proportion of foodborne pathogens are maintained, increased, and effectively distributed. Illness will develop when people working in restaurants, nursing homes, and hotels and private citizens handle food incorrectly or inadequately. Our programs and intentions do not ignore this but do not provide the proper weight. It is cheaper, simpler, and more effective to prevent foodborne diseases at the final level of preparation than at any other point in the food chain. It is essential to say this, repeat it, teach it, and let it become an article of faith and a base of our practice.

There are problems in this approach: people demand to be risk free, some want to blame others, mothers no longer teach children the basics of food hygiene, and the food-service industry has legendary labor problems. So be it. Let us explain the problem and use our resources to teach policy makers, allied scientists, food handlers, and families. This is not the stuff of high research, complex organizations, and multimillion dollar programs of investigation. It is simple effectiveness, healthwise and costwise, and good science. To do otherwise is to use good science to improper ends.

REF: JAVMA, 208(12), June 15, 1996.

-----------------------

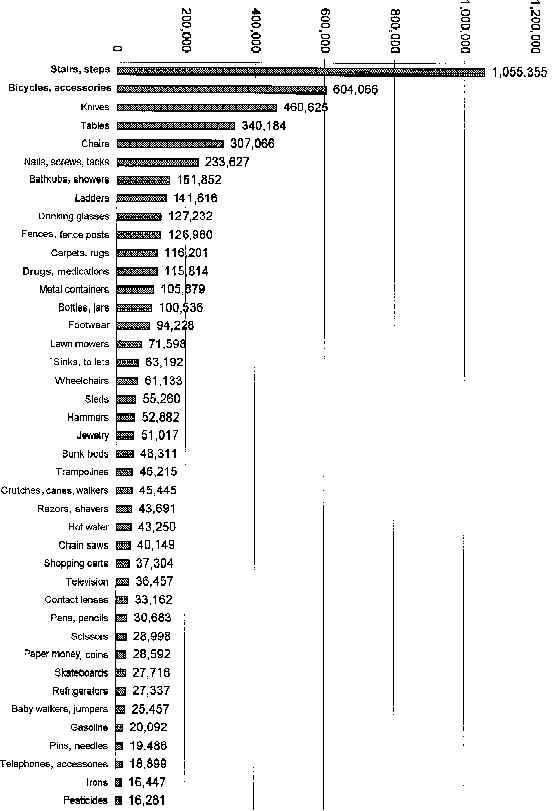

Estimated Injuries in the U.S. from Selected Products -- 1993

Note: These national estimates are based on injuries treated in hospital emergency rooms participating in the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System. Patients said their injuries were related to the products; this does not necessarily mean the injuries were caused by the products.

REF: Agricultural and Environmental News, Issue No. 125, July 1996.

Art Craigmill

Extension Toxicologist

UC Davis